I love people who do pro bono work. They offer their skills free of charge for something they believe in. They will inherit the earth.

My son Charlie, training to be a human rights lawyer, works pro bono on Fridays for Reprieve on ‘death row’ cases and at weekends for people who need legal aid. He does this gladly as it helps him learn his trade. He does it for good causes because he figures they need and value his services more than would, say, a big corporate client or its highly paid legal firm. He not only learns from this, he’s convinced it’s well worth doing.

In my time I’ve worked with great agencies and individuals all of whom give the same great service; and, at times, do it pro bono. Usually, they worked unpaid for a reason. Sometimes it’s commercial, even though no money changes hands – it looks good in their client portfolio, it helps open doors, it smoothes a passage. Sometimes they do it because in their already busy lives they really care passionately enough about some cause to work for it for a while for no pay.

Great people, doing a great thing. Heck, I’ve even been known to work pro bono myself, from time to time. So, why do so many requests from charities for free work get right up my nose?

You know the kind of thing – see opposite, based on a recent real example except only that the name and some minor details have been changed. I get emails like this far too often. My response is always the same.

Robert Cialdini and his seminal book.

Such requests depress me simply because in the proposed arrangement there is not even a hint of mutual, reciprocal benefit, but an assumption that I’ll want to do it all the same. So many people in not-for-profit organisations seem unaware of, far less appreciative of, the paramount importance in this kind of deal of reciprocity, of getting people to want to do something for you because it chimes with their needs and desires too; because it’s in their interests to do it, even if it only satisfies their most basic charitable drive.

Dr Robert Cialdini describes the impulses behind these decisions in his direction-changer of a book from the mid 1980s, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. As these pro bono requests fail to offer reciprocity or even to satisfy any of Cialdini’s five other key aspects of asking, they are usually doomed to failure. There’s a good lesson in this, for fundraisers and for clients.

Even when I had a large and prosperous agency behind me I was reluctant to accede to such requests. To put it simply, pro bono or not, someone has to pay for my time and expertise. And if it isn’t the organisation that’s benefiting from them then the cost, inevitably, is being passed on to someone else up or down the line. I worry that it’s the paying clients of those that regularly do pro bono work who are really paying for it, through higher-than-they-should-be fees.

How I should reply to such a request now is shown opposite.

Writing a reply like this makes me feel bad. It probably makes the recipient feel bad. But because it lacks reciprocity the original request is bad fundraising. Even if there were some recognition of what the request might involve for me I might still decline. But neither the writer nor I would need to feel bad about it.

When I worked in publishing the best advice I was ever given was, never assume. Our old production director had these two words printed large and stuck on the office wall. If it were legal he would have had them tattooed on our foreheads. But their observance saved much embarrassment and heartache, plus many mistakes.

It’s sound advice not just for editors but for anyone.

In similar spirit I’d like now to offer a two-word exhortation to charities in the hope they might avoid all that and much injustice too. Never presume. Or put another way, please don’t ask for something, particularly a really major gift, unless you can justify the gift not just in terms of what it means to you, but in terms of what it can give, to the donor.

© Ken Burnett 2010.

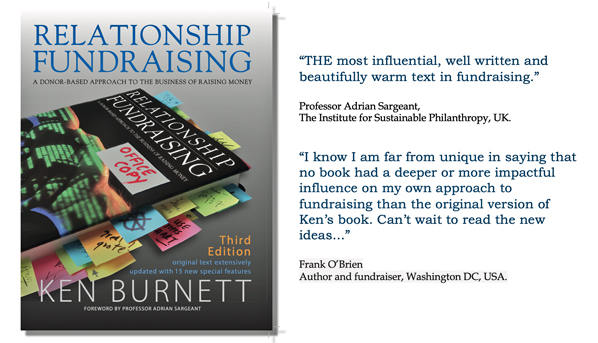

At the time of writing this blog Ken Burnett had more than three decades experience as a client, agency head, consultant and adviser to fundraising agencies and clients around the world. His books on fundraising and communication include three editions of the classic Relationship Fundraising: a donor-based approach to the business of raising money (1992, 2002, and 2024), The Zen of Fundraising and more. Fill the gaps in your library here.