The first of this series appeared in November 2014 and the final part was published in mid-May 2015. At no time in my long career as a fundraising direct marketer have I ever met a donor who wanted to be marketed at. Nor, if I’m honest, did I ever expect to. The massive fundraising machines we created now demand constantly to be fed. And their appetites are huge. Intro Part 1 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

You can order

|

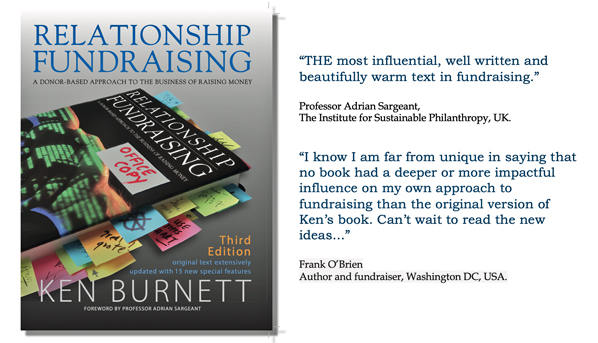

My career was built on marketing. I’ve loved it, and I still do. So it pains me greatly now to admit this: for fundraisers, marketing was a mistake. I can feel the knives of other fundraising pundits being sharpened as I write. ‘What on earth are you saying, Burnett? The hand of marketing has fed you fulsomely for decades. How can you turn round and bite it now?’ For sure marketing seems great for charities. In the 1970s, 80s and 90s a fresh wind fed by direct marketing allowed fundraisers to recruit donors by the shedload. Those generous people pressed into regular support of our organisations brought with their direct debits a bedrock of solid financial dependability that sustained our great national and international causes through whatever challenges came their way. And is still doing so. Clearly marketing has many benefits. Why would it not be right for fundraisers? The advantages I don’t deny. There’s just one huge problem. Donors don’t like marketing. No, that’s not strong enough. Donors fear and mistrust it. Marketing involves selling and persuasion. Donors don’t want the causes they believe in to sell to them. They don’t like to be interrupted by us and they don’t want to be irritated either. As I survey our sorry retention statistics, the rising cost of acquisition and the decline in public warmth for and belief in our organisations and how we do business, I’ve become convinced that marketing really was a mistake. At no time in my long career as a fundraising direct marketer have I ever met a donor who wanted to be marketed at. Nor, if I’m honest, did I ever expect to. I’ve yet to meet a committed donor who believes there’s any good purpose in his, or her, being pushed or persuaded to give. Most donors (and I’ve met more than few) quickly make it plain they’re antipathetic at best to our marketing ways and downright suspicious of any selling strategy from those causes that they believe in. So why do we persist with marketing at our donors as if it were the unchallengeable fundraising norm? Could there be a clue here as to why we are losing supporters as fast as we find them, at massive, still growing cost? There was a moment in the 1960s or 70s when, for communicating with its publics, the nascent, blossoming activity of charity fundraising opted to embrace wholesale the techniques and approaches of commercial marketing. Influential, enthusiastic voices were raised extolling the wonders of direct marketing, mine amongst them. In those days you could recruit donors at a profit so causes for concern, if they were there at all, were hard to spot. Though as ever more charities came to recognise that marketing was a golden goose, this began to change. The headline at the top of this page isn’t entirely the result of some sudden Damascene conversion. I’ve long been concerned as to how fundraisers do marketing. At the turn of the 1980s I wrote a book called Relationship Fundraising in the hope of countering the then prevailing ‘churn and burn’ paradigm, which focused on the money rather than the people sending it. But my fundraising vision was still not based on what the donor wants. I ran a direct marketing agency. Though I tried to switch its focus towards communication I still described our enterprise as marketing and communication specialists, putting marketing first. Why was marketing a mistake? Because our very success at it has enabled us to downplay the donor experience, which is what we should have focused on to build the long-term 40-year-plus relationships we need. As a result we’re haemorrhaging our lifeblood while paying a fortune in acquisition just to stand still. The escalating cost of acquisition has now, in places, reached proportions impossible to justify unless we succeed in keeping donors a lot longer. Yet despite persistent protestations of being donor-led and a few inspirational examples of relationship fundraising our sector seems locked into the ‘you give, we get’ mindset, with the fundraising equivalent of persistent hard selling the norm and brilliant customer experiences the hard-to-find exception. As professor Jen Shang at the Centre for Sustainable Philanthropy has said, in understanding the psychology of philanthropy the WHY is the only true way of enhancing its practice. Or as Tom Belford in The Agitator put it, ‘How will your organization best enable me to make the difference I want to make?’ For sure the graphic opposite from Linton and Stein describes more accurately than any marketing strategy what fundraisers should be offering their supporters. It’s why Roger Craver, author of Retention Fundraising, exhorts us to ‘...focus clearly on the ‘WHY’ of donor motivation and loyalty and redefine “marketing” not as “selling” to donors but as the exploration and discovery of donor interests, preferences and intent.’ Amen. Maybe we need a different kind of fundraiser, more raised on the skills of passionate emotional storytelling and less on spreadsheets and fundraising from behind a desk. All, of course, need to be consummate communicators and adept, large volume inspirers across all media and donor types. Even without marketing, or with marketing without the selling, this job will be no easy option. Improving the donor experience Should we be asking for £2.00 a month or £25 a month? Is the future direct mail or digital? When we flood the streets and doorsteps of Britain with teams of fundraisers is our priority to reach our acquisition targets or to give potential donors the best possible experience of our cause and their role in it? Difficult questions, of course. But are they the wrong questions altogether? It seems to me and others too that what’s missing is emphasis on the WHY and the pleasure of being a donor. Low rates of retention and the declining standing of major charities are obvious barometers of our failure to truly inspire our publics.The large-scale public fundraising paradigm we now see seems to me more obviously flawed than ever. I wish the marketing and communications agency I started in the 1980s had emphasised passionate commitment, reciprocity and feedback a lot more strongly than techniques for marketing. I wish my books had stressed the special, mutually beneficial nature of our customer relationship more than how we might maximise sales to them. I wish my lectures and seminars had been less about marketing, particularly legacy (bequest) marketing, and more about inspirational storytelling and the joy of giving. Because with hindsight I now see that, for fundraisers as well as for donors, marketing was a mistake. © Ken Burnett 2015 Please feel free to email me your comments here. This analysis of the future of fundraising is in five parts: See also the forewords to two important fundraising books published in 2015, Retention Fundraising by Roger M Craver and How to love your donors (to death) by Stephen Pidgeon, here. |

For more than three decades I devoted my working life to the direct marketing of good causes, building future fundraising income for a variety of charities by recruiting regular low- to mid-level donors often in their hundreds of thousands. The massive fundraising machines we created now demand constantly to be fed. And their appetites are huge. The challenge now is, how could we move to a much better customer experience for low to mid-level donors without huge investment and without disrupting the income flows that keep these machines alive? I’ve tried to point out some possibilities in the other articles in this series.*

* The development that seems to me to have most potential for transforming our business will be found in the steady stream of discoveries from the behavioural science community that indicate that giving to a charity really is very good for you. See my later seminars on the future of fundraising, on SOFII, here. As you’re nearing the end of this series here’s a little present for you from the legendary Sam Cooke, ‘Change gonna come’.

|