|

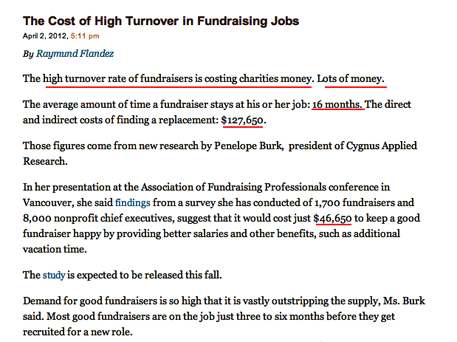

Blog 11th July 2012 ...the average stay for a fundraiser in the USA is just 16 months and the cost to replace each one averages $127,650. This is serious expense on top of mega-disruption for their fundraising organisations.

Home page.

For some rare pieces |

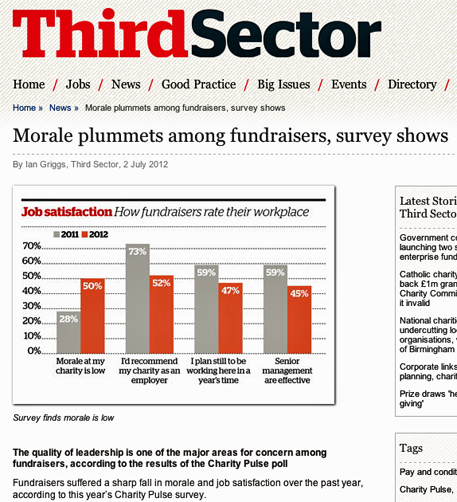

Oh dear, more bad news this week about the troubled state of mind of those fragile, sensitive possums, Britain’s young fundraisers. According to a Charity Pulse survey recently trumpeted in the estimable Third Sector magazine, morale at the younger end of our profession has slumped to a new low. Here are some of their key findings:

Aah, bless them! These are hard times of course but even so, this slide in job satisfaction among the young seems extraordinary. No wonder they’re troubled. Maybe the rest of us should be too. In the UK it’s broadly assumed that fundraisers stay in post on average just 18 months before moving up or, more often, upping sticks – going elsewhere to secure better recognition, pay and conditions. I can’t prove the statistic but suspect it’s reasonably accurate. Research doyenne Penelope Burk recently reported (see opposite) that the average stay for a fundraiser in the USA is just 16 months and that, all in, the overall cost to replace each one averages $127,650. This is serious expense on top of mega-disruption for their fundraising organisations. Apparently, Penelope goes on to explain, keeping rather than replacing the movers would cost much less, on average just $46,650, if invested prudently in better salaries, work conditions and more holiday time. So not investing enough to keep and retain the best seems to be a false economy of some scale. Calamitous even. Unless this slide is arrested morale, already alarmingly low, seems set to sink still further. While there’s not likely to be an easy or total solution to this it’s a no brainer that collectively and individually our sector leaders should all be doing a lot more to stop the drain. For one thing (see the twin secrets of fundraising success) it’s impossible for most long-term fundraising plans to be conceived or realised if the people who must implement them aren’t around long enough to get them started, far less steer them to fruition. So what could we do?

That’s just for starters. I’m sure a sector as creative and imaginative as ours can come up with many innovative ideas to turn the tide, stem the flow and make the voluntary sector the shining exception, the one sector where everyone wants to stay put because where they work is so great. Come to think of it though, I don’t know why this inability to invest in systems that nurture and develop our best staff should so shock me. As we know to our cost charities are much less good than they should be at attracting, inspiring and retaining donors in all their variety. So it’s perhaps not surprising at all that fundraisers too should be lapsing and attritting by the shedload. Seems we never learn. © Ken Burnett 2012 PS Before you write, I use the phoney verb to attrit here very much with tongue in cheek, in the hope that I’ll discourage its use. Though I fear the irony will be lost on many. Needless to say, they’re the ones who shouldn’t get that pay rise, more holidays or indeed any perks other than being shown the door to, perhaps, a career where how you communicate doesn’t matter. For more from Charity Pulse about what fundraisers themselves are telling us about the state of their morale, see here.

|

We know to our cost that charities are much less good than they should be at attracting, inspiring and retaining donors in all their variety. So it’s perhaps not surprising that fundraisers too should be ‘lapsing and attritting’

Reader’s comment Reader Nicola Tallett, fundraising and marketing director at the UK’s MS Society, has written to point out that low morale in a fundraising team is often linked to one or more individual’s inability to deliver. While their colleagues aim high and dream big, they just want an easy time doing what they always did, so they’re frustrated. And the more their colleagues thrive, the more their morale sags.

|