|

Archived article No 6 I wrote for the USA journal Contributions magazine every two months for nearly six years. This was the first article I ever wrote for them. It compares and contrasts with a somewhat more positive piece that I wrote ten years later, see here, immediately after Christmas 2011.

She’s from a generation that takes these kind of things at face value, trusting organisations that do so much good to be sincere, honest and worth listening to. She believed in them. But, of course, they were marketing to her. To them, she was just a name on a list. She was a statistic. A target.

So the junk phone call has entered our vocabulary and donors dread the ringing phone as much as they fear the postman’s tread.

Also from Ken’s article archive,

|

I’m writing this at the beginning of January 2001, having just survived another festive season with its traditional bonhomie, over-consumption, family visits and, of course, surfeit of charitable appeals. Christmas is still a time for giving and so remains the fundraiser’s favourite – and presumably most effective – time for asking. So this year, as I’m sure you did too (for effective fundraisers have to be donors too, don’t they?), I found myself on the receiving end of many, many fundraising appeals. Most I looked upon favourably, if not necessarily financially. Some, I found rather worrying. And a few, I confess, really scared me. That’s what I thought I’d write about now. Some 300 years ago the philosopher Rousseau wrote about being a donor.

Jean Jacques Rousseau, Though written more than three centuries ago, today many donors would still agree with Rousseau. Being a donor can be grim. I must tell you about a recent visit to my mother at her home in the Scottish Highlands. My mum is now in her mid-eighties and not nearly such an active charity supporter as she used to be (she lives on a fixed income and inflation has hit her hard).Through no fault of hers, she can’t now help the organisations she supported all her life – the animal charities and the children’s home which still mean a tremendous amount to her. During her long years supporting a range of worthwhile causes, my mum unfortunately got herself onto quite a few mailing lists. Whenever she received a letter calling on her for help my mum took it very seriously. She’s from a generation that takes these kind of things at face value, trusting organisations that do so much good to be sincere, honest and worth listening to. She believed in them. But, of course, they were marketing to her. To them, she was just a name on a list. She was a statistic. A target. Now, I don’t think she believes as much as she once did in the national charities she’s supported all her life. I discovered this when I noticed a pile of unopened mail on the table in her hallway. On examination it turned out to be several appeal mailings, from various charities. Well, my mum’s not stupid and because the formulae of fundraising direct marketing are so transparent and obvious, it seems it wasn’t long before she began to realise what they were doing. That’s why the mail in her hallway was languishing unopened. She uses phrases like ‘I just get too many of these appeals’, or ‘I can’t support them all, you know’. But really she has stopped taking what they were saying seriously. She has stopped believing in them. Even to the point of not even bothering to hear what they have to say. I suspect there are tens of thousands like her – people who for natural reasons have paused in their giving. People fundraisers think of as lapsed donors, and bombard with appeals. Mother’s disdain for the flood of charitable appeals she receives has coloured my own view of charity direct mail appeals. Surely we fundraisers could be more distinctive and original – and so more welcomed – when we write? Christmas is all about…shopping Strolling pedestrians now can scarcely walk a hundred yards in many of their favourite shopping malls without being bushwhacked by an anorak-clad, clipboard-wielding youth from Amnesty or Greenpeace or the Imperial Cancer Research Fund or such like, intent on persuading any passer-by prepared to pause long enough to be signed up to regular, monthly committed giving by direct debit. This fundraising technique works well – for now. Imagine how popular it will be with our publics when hundreds of fundraising organisations have jumped on this latest bandwagon. Pedestrians and shopkeepers in Edinburgh’s fashionable Princes Street recently fronted a TV consumer programme called ‘Watchdog’ to bemoan their inability to move along their favourite mile without being hassled by fundraisers. I have found that ‘No habla Inglese’ is the most effective response. But is this really how fundraisers want to be viewed by the public? Are we not in danger of becoming as popular as tax inspectors, traffic wardens and timeshare salespeople? In some quarters, I’m sure, we’d be lucky to be held in such affection… While I’m being critical of fundraising communication, what about another favourite child of UK fundraisers, the door drop, or household delivery as it is also known? The block of flats where I stay when in London is clearly high on most fundraiser’s lists of favourite targets for door drops – unaddressed and barely targeted mail. I get two or three unaddressed pieces of fundraising mail each week through my door. Often they’re accompanied by the gift of a cheap pen, and perhaps a phoney questionnaire. Otherwise, they’re almost indistinguishable one from the other. This is because, like charity direct mail, they all follow the standard formulae for fundraising communication that have been adopted hook, line and sinker by the fundraising profession. This is indiscriminate mass marketing of course, which is unforgivable in these days of sophisticated database segmentation. But it’s cheap. And at even half a per cent response, it pays. Door drops are on a par with those awful loose inserts that fall out of your Sunday newspapers. When they started they were fun, interesting even. Week after week they quickly become intrusive and irritating. And they make a lot of litter. Then, I hear you say, what of that instrument of misery or joy, the telephone? In the UK in recent years fundraisers have turned in increasing numbers and with increasing enthusiasm towards the telephone as a new medium for reaching large numbers of people effectively. The telephone is an intimate, one-to-one communication device, so it should be ideal for sensitive relationship building. Instead fundraisers have used it as a blunt instrument of mass marketing to bludgeon their donors . Having first fabricated ham-fisted excuses for calling, they have then led their hapless donors through deathly scripts, usually read by unsurprisingly out-of-work actors with about as much enthusiasm as a pig has for a ham sandwich and a lot less commitment – in fact, they’ve telemarketed at their donors en mass rather than seeing the telephone as a convenient device for getting directly in touch with their friends – you wouldn’t telemarket your friends, would you? So the junk phone call has entered our vocabulary and donors dread the ringing phone as much as they fear the postman’s tread. I don’t know if there are more charity calls at Christmas, but I do know donors who are sincerely grateful for their answering machine and automatic number recognition. Even television has been used to sell good causes exactly like they were soap powder. In short we’ve become very efficient mass marketers. We’ve swapped sincerity for technique. And our publics can recognise this quite easily. The point of all this – and it came to me fairly strongly this Christmas – is that we fundraisers communicate rather badly. Particularly considering the wealth of material we can draw upon to inspire interest . Surely we have the best stories in the world to tell – real drama, urgent needs, touching human interest, life and death issues… Is a free plastic pen really the best inspiration we can give to coax a potential new supporter? How others see us According to Henley, the public’s trust in charities has been declining steadily over the past decade at least (we’re only just above the media and the Church – it’s that bad!). The other research was conducted by several respected groups following the actions of campaigning charities at the World Trade Organisation’s famous Seattle meetings in 1999. This survey found that the majority of a cross section of people aged 34-64 in the USA, France, Germany, the UK and other countries believe NGOs (non-governmental organisations) are more credible than commercial organisations, more trustworthy, more likely to take action on the public’s behalf and much more likely to be effective. When we get it right, people really are prepared to believe we can make the world a better place. But as many donors will tell you, we too often get it wrong. Short-term gain, long-term suicide What we do rely on is the way the public perceives us through our regular communication with them. Unfortunately, unless the communications output of our profession dramatically improves, as soon as Seattle is forgotten we’ll revert to the gradual erosion of public trust, respect and support that is the inevitable outcome of trivial ‘lowest common denominator’ mass marketing. Why do we do this? Well, I guess it’s because most of our organisations (and responsibility for this must rest with boards and CEOs) still find it easier and preferable to go for short term, rapid payback rather than to lay the foundations of meaningful, long term donor relationships. That last phrase, by the way, is the light at the end of this particular tunnel. There are alternatives. There’s a huge amount we can all do, to communicate more welcomely, more meaningfully and more effectively with all of our donors. But I’ll leave that for future articles. © Ken Burnett 2012 This article has been adapted from a piece that first appeared in 2001 in Contributions Magazine, USA.

|

Disagree with me? Or agree? If you’ve anything to add, have your say here. Email your thoughts or comments now to me and providing they’re relevant and appropriate I’ll put them on the site. Sign up here for more OPINIONS coming soon

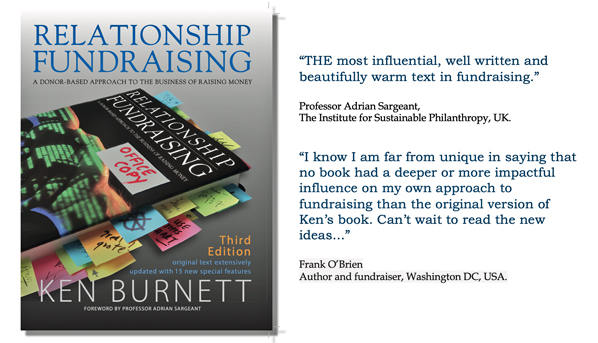

Ken Burnett is co-founder of Clayton Burnett Limited, a director of The White Lion Press Limited and he’s a former chairman of the board of trustees at the international development charity ActionAid. He’s author of several books including Relationship Fundraising and The Zen of Fundraising and is managing trustee of SOFII, The Showcase of Fundraising Innovation and Inspiration. For more on Ken’s books please click here.

|

Telephone, mail or face-to-face; donors glumly endure the same grim experience at the hands of professional fundraisers.

Telephone, mail or face-to-face; donors glumly endure the same grim experience at the hands of professional fundraisers.

The spirit of Christmas is about giving. You might expect us to have moved on since Scrooge got his come-uppance, but often it doesn’t seem like it.

The spirit of Christmas is about giving. You might expect us to have moved on since Scrooge got his come-uppance, but often it doesn’t seem like it.