Archived article No 13 Could this be an opportunity for fundraisers?

Also from Ken’s article archive,

|

I wonder if, like me, you sometimes feel this modern world is going just too fast? Perhaps, as I am, you’re increasingly coming to doubt that the many technological advances of our times are actually making our lives easier and better, like they promised they would? By any chance, does your daily email mountain also seem to you ever harder to climb and less interesting to boot, as mine does? Or does it trouble you, as it does me, that while you can now be reached by telephone pretty much wherever you happen to be, this additional intrusion hasn’t really made you more effective, more efficient and, more importantly, happier, as it should have done? If any of the above doubts apply, you’re not alone. It seems there’s no escape, as yet. But a means may be coming. Fundraisers who feel particularly cursed by the go-faster society should read a book called In Praise of Slow by Carl Honoré (Orion Press 2004). Carl has set himself on a mission against the cult of speed. He promotes what he claims is rapidly becoming a worldwide movement: the campaign for slow, which advocates among other things slow food, a better life/work balance, more green spaces, pedestrian-only zones, areas devoted to calm and tranquillity, and taking time to read proper bedtime stories to your kids. Carl thinks the trend towards calm will catch on – slowly (some years back the slow food campaign claimed 78,000 members in 50 countries). Fundraisers could find advantage in the progress paradox Does this possible misconception, perhaps, present just the kind of opportunity that today’s fundraisers should be grabbing eagerly with both hands? Fundraisers as much as anyone operate in a fast-changing business and social environment. Some of the consequences of this are surprising and will open up opportunities hitherto not even guessed at for those who would fundraise. Massive upheavals that we are already starting to see may lead to as yet undreamed-of chances for the nonprofit sector. But like all opportunities we have to spot them in time and exploit them to the full. The progress paradox, I submit, is one of these. Progress might not be making our species happier. These days our society’s unease may not be coming as it traditionally has, from endemic poverty, from our people having to go without, so much as from our prosperity, our being increasingly able to go ‘with’. General affluence, it appears, does not automatically arrive in the company of general contentment. It’s in the most affluent of societies that one finds the longest queues outside the psychiatrists’ doors. Affluent people in a rush are most likely to head that queue. But the risk to these time-poor rich people comes not from fundraisers, in fact quite the reverse. Fundraisers might be just the people to solve the biggest of their perceived problems. According to Robert Samuelson writing in Newsweek, as living standards improve people don’t necessarily feel the benefits. Although folk like us now averagely start work later in life, are retiring earlier (well, some still are) and in reality have oodles more time than our ancestors, we persist in feeling time poor. Obesity is as large a health risk for the affluent as going hungry is for the poor and, like poverty in the developing world, it’s growing in our society. Instead of more money making us happier, griping apparently rises with income. It’s a world turned, apparently, on its head. It seems more and more people find that with increasing affluence comes a decreasing sense of fulfilment. Maybe as we cease to need to worry about basic survival, other issues of purpose and fulfilment crowd in on us. Look! We offer meaning… Think about it. What could be more appropriate for affluent people in a hurry than fundraisers, who can make it easy for people to find useful, worthwhile and interesting homes for their excess money without any pressure, fuss, hassle, or onerous time commitment? We could soon build for ourselves a reputation as the people to turn to when the pressures of modern affluence become too much to bear. This might be a better role for the fundraiser than that which he or she currently enjoys – a role as provider of fulfilment for busy people on the move. Postscript – on doing without As I explained at the outset of this piece I’m a little disillusioned with the so-called technological advances of recent years. But the wonder of modern gadgetry and gimmickry is how good you feel when you do without them. This reminds me of the story of the rabbi and the poor man who lived in one small room with his wife and three children. ‘I can’t stand it!’ wailed the man. ‘What can I do?’ The rabbi told him to get a dog. The dog barked at the children and messed up the floor. Then the rabbi suggested he get some hens. The dog chased the hens, which frightened the baby. ‘Get a goat’ insisted the rabbi. And so on, until the rabbi added a horse and the whole thing became completely impossible. ‘Now, get rid of them all,’ said the rabbi, ‘and tell me how you feel.’ ‘It‘s wonderful!’ cried the man in gratitude. ‘There’s just me and the wife and the children, and we have the whole room to ourselves.’ Possibly the gadget we really need is the one that we can programme to get rid of all the others. All progress may indeed be in the hands of unreasonable people, but it seems to me that the rest of us should reserve a healthy scepticism for all changes and, supposed, advances. To underline this point let me end with a quote from a perhaps unlikely source, which at first glance appears to contradict my opening remarks.

Ian Malcolm, the mathematician in Michael Crichton’s Evidence perhaps that in reality we have made no progress whatsoever. But I suspect that 30,000 years ago, while the men had all that time to play, sleep, or whatever, the women still had to spend just as long doing the housework. Plus ça change. © Ken Burnett 2013. This article is adapted from a piece that ran in Contributions Magazine USA in 2004 and on the Guardian Abroad website, 2007.

|

The liberating joy of a walk among the cherry blossoms. The invisible, imaginary line that was implied by my physical distance meant that I could play with my kids while others were working, which I loved. Or I could take my dogs for long walks in the early mornings while my colleagues endured commutes by tube, bus and train to their daily grind, or wrestled with technology that hadn’t quite caught up with me yet. Some years back I visited Greenpeace in Washington with their international director of fundraising, from Amsterdam. He had 13 emails waiting while I, an email virgin, had none. So while he toiled indoors I went for a long walk outside. It was cherry blossom time in DC then – lovely! Then in rapid succession to my French fortress came email, the Internet, mobile phones and lower call charges. And conference calls. And FedEx and DHL. And, I suppose, our society’s increasing familiarity and ease with modern technology, matched by a growing impatience in our species that means nothing can be waited for, gratification has to be instant, responses have to be now, or next day at the latest. From these miracles of modern communication there is no escape, for in these busy, competitive times everything is a race against the clock.

Disagree with me? Or agree? If you’ve anything to add, have your say here. Email your thoughts or comments now to me and providing they’re relevant and appropriate I’ll put them on the site. Sign up here for more OPINIONS coming soon

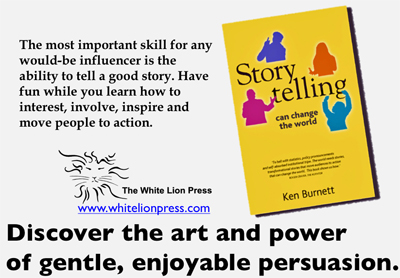

Ken Burnett is co-founder of Clayton Burnett Limited and a director of The White Lion Press Limited. He was chairman of the board of trustees of the international development charityActionAid from 1998 to 2003. Ken is author of several books including Relationship Fundraising and The Zen of Fundraising and is managing trustee of SOFII, The Showcase of Fundraising Innovation and Inspiration. For more on Ken’s books please click here.

Ken’s latest book Storytelling can change the world

|